Data privacy: Navigating Data Collection in an Increasingly Complex Regulatory Landscape

Data is the new oil. Some have even compared it to nuclear power. Metaphors aside, data and its uses are transforming the world we live in. Algorithms, analytics, and applications are changing every field of human life. But, just like oil – data has its downsides. One major concern about the increasing thirst for data is how to maintain privacy and confidentiality as companies and governments search for more and more information about more and more people. In many ways, these conversations are arising too late in the game. Privacy in the age of the internet has been severely damaged. Over half of all Americans are already in facial recognition databases. 80% of social media users are concerned about businesses accessing the data they share on social media platforms. 95% of Americans are concerned about businesses collecting and selling their personal information without permission.

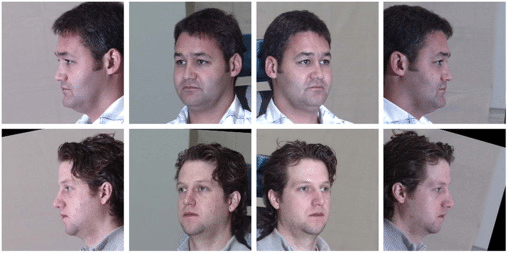

In the field of Computer Vision, the ability to recognize objects is reliant on the processing and consumption of huge numbers of images (data) of the object in question. This appetite is only increasing as CV systems become increasingly complex. In the early days of computer vision, researchers paid subjects to have their photos taken in different poses and lighting settings. They would come to a lab, sign legal consent forms and be photographed. This process was time-consuming, expensive, and not scalable. These early datasets were limited in scope and in efficiency.

In This Article

Scraping Begins

With the rise of the internet in the 2000s, researchers could access billions of images, including millions of photos of people, with simple scripts. Researchers began to “scrape” faces from Facebook, Wikipedia, Google, and Youtube videos. One example of this is IBM’s ‘Diversity in Faces’ Dataset. In order to create the dataset, IBM used a collection of 100 Million images released with a Creative Commons license that Yahoo issued in 2014. These images were initially uploaded to Flickr and were gathered into the database without the express permission of the photographers and people photographed, although the publication was technically legal under Flickr’s terms of use. Despite assurances that users could opt-out of the database, NBC discovered it’s nearly impossible to get images deleted from the public database. There are numerous other examples of image datasets that have scraped from the internet, such as MegaFace, CelebFaces, and Faces in the Wild. Many of these training datasets have been compiled without explicit permission and consent.

Still, these databases are often not sufficient for certain training tasks and so companies have gotten “creative” in how they supplement or build their own datasets. One scandal involving ethically murky data collecting tactics involved Google. Google employees were sent to ask for voluntary face scans in exchange for $5 gift cards. The employees were encouraged to hurry subjects through consent forms and survey questions. Specifically, they were directed to ‘target’ low-income people and African Americans. The agreement the subjects signed gave Google sweeping permission to use the images with few limitations. Aside from raising serious legal questions, this morally questionable activity created a backlash of bad publicity against Google.

This backlash, though over an extreme example, demonstrates public sensitivities towards data collection. It also demonstrates how desperately companies like Google need data. Increasingly, these public concerns have begun to be translated into legal frameworks. New regulations and laws that protect privacy and transfers of data are creating new, overlapping and complex frameworks of regulation that companies must navigate.

Read our eBook on Solving Privacy Concerns with Synthetic Data. Download now.

Privacy Laws

A fairly recent legal development, privacy laws – many of which include limits on how the information about private individuals can be used – have now been enacted in over 80 countries around the world.

In 2018, the EU implemented the General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR). The GDPR is the most comprehensive and protective digital privacy regulation in the world. Under the GDPR, all companies that collect and process data are required to establish a legitimate legal basis for processing personal data. Sensitive data is a special category of personal data that is subject to additional protections. The GDPR defines sensitive data as: ‘personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioral characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images.’ Datasets of images of humans clearly are sensitive data and require a higher level of compliance and scrutiny. However, the GDPR is still new – there have been limited enforcement actions to give companies a sense of how to interpret key sections. While many companies are striving to uphold the principles of the GDPR to the best of their ability, there are still gray areas that, as they are gradually defined through regulatory actions, could further limit and curtail data collection and processing activities.

Another recent example of privacy policy regulation is the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) that became law in 2018. Under the CCPA California residents have the right to demand a business to disclose personal information they have about them, and to have the data deleted. Additionally, it regulates data collection and requires a more stringent process. In November 2020, California voters approved a new privacy law, the CPRA. The CPRA is even more stringent than the CCPA, and tacks closely to the GDPR. While the CPRA as a whole will not go into effect until January 1, 2023 it clearly signifies a trend. Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) is Canada’s main national law regulating privacy in the private sector and is meant to bring GDPR style regulation to Canada. Worldwide, countries are working to match their own privacy laws to the standards of the GDPR.

Compliance with these rules is extremely challenging. The GDPR is 88 pages of complex and technical legalese. The different regulations have different rules depending on the size of the company, geographical location and citizenship of the individual whose data has been collected. Abiding by the rules becomes even trickier when collecting large, unbiased datasets from different countries worldwide and then transferring that data between countries. Chapter 5 of the GDPR deals specifically with the issue of transferring data. With increasing legislation worldwide navigating the complex web of regulation becomes very complicated.

What do I need to gather a dataset?

While this is not legal advice, these are some of the common things to look into and be cognizant of if intending to gather a dataset with sensitive (human) images.

- Informed, Specific Consent – This requires consent to be given by a clear affirmative act establishing a freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the subject’s agreement to the processing of their personal data.

- Documentation – You must keep records documenting the informed consent procedure, including the information sheets and consent forms provided to research participants, and the acquisition of their consent to data processing. These may be requested by data subjects, funding agencies or data protection supervisory authorities

- Data Security – You are required to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure a level of data security that is commensurate to the risks faced by the data subjects in the event of unauthorized access to, or disclosure, accidental deletion or destruction of, their data.

For a high-level overview, take a look at the GDPR’s Compliance Checklist.

Looking Ahead

More and more countries are introducing privacy laws regulating industry practices. The GDPR has become the standard that countries are emulating and using as a baseline as they mold their own legislation. A rapidly evolving data privacy landscape requires attention and resources. According to Gartner, by 2023, 65% of the World’s Population will have their personal data covered under modern privacy regulations, compared to 10% in 2020. This promises to make collecting data manually even more complex, especially when data has to be collected from multiple geographies in order to achieve desired diversity and combat bias. Companies are increasingly hiring talent specifically to oversee this type of process and compliance; by the end of 2022, more than 1 million organizations will have appointed a privacy officer. For teams in the Computer Vision space, specifically in the context of humans, these developments are a tectonic shift and require preparation and planning ahead.

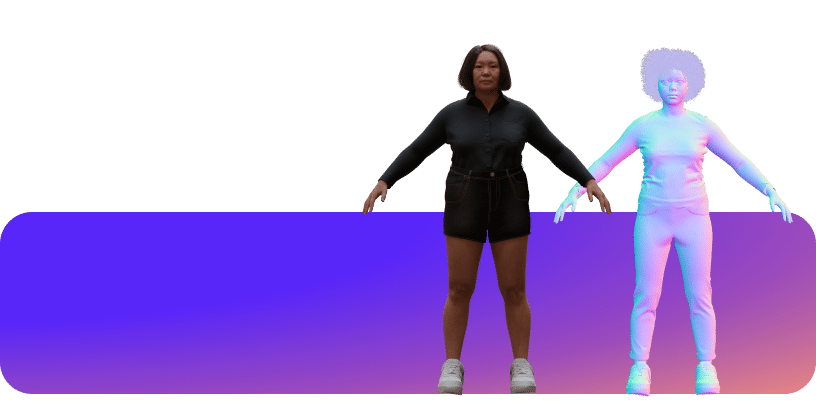

Simulated Data can offer a promising and much-needed solution to the problem described above. Simulated Data generates huge datasets off a miniscule number of real data points. So the need to collect real data is decreased exponentially, saving time, money and limiting the need to comply with all the complex regulation detailed above. Additionally, the end dataset contains no real, personal and sensitive data because all the data provided by Datagen to end users is generated synthetically, free of any personal identifiers. This allows us to centralize all compliance with privacy regulation in-house and at a small scale. Our product enables our partners to focus on achieving their development goals without spending time navigating an increasingly complex web of international regulation.

Read our eBook on Solving Privacy Concerns with Synthetic Data. Download now.